The Walkabout Director

One Technique for Better Live Surgical Video Broadcasts

Anyone who has ever toured a television studio can tell you that the SCR (studio control room) is typically walled off from the stage and audience in a sound tight room, often over-looking the stage like a skybox at a football game. The BBC originally coined this skybox “the gallery,” not to be mistaken with peanut gallery, which is what an audience is sometimes called. (Peanut gallery possibly came from the circus of lore, when onlookers discarded the salty husks of devoured peanuts where they sat).

The television studio gallery is where the composition and camera mixing takes place during a live broadcast. It is where the director takes the helm of the program and barks out the shots and camera angles necessary for any given program.

By design there are many good reasons why the gallery must be isolated from the stage area. Most technical reasons are obvious—noise and light isolation, and a room in which talking amongst the crew does not disturb the audience or talent.

But not only is the gallery the encephalon of a live production but it couples technical expertise with the director in the same shoulder-to-shoulder location, giving live production optimal efficiency. Who hasn’t seen movies like Broadcast News or Network (am I dating myself?), the feverish dramas that loop through the gallery?

Surgical Broadcasts: A Different Animal with Different Requirements

Television studios have perfected the best of all possible worlds of a live video configuration. However, when the live event goes on location, television professionals mostly employ the same thinking about the studio configuration and apply it to the location.

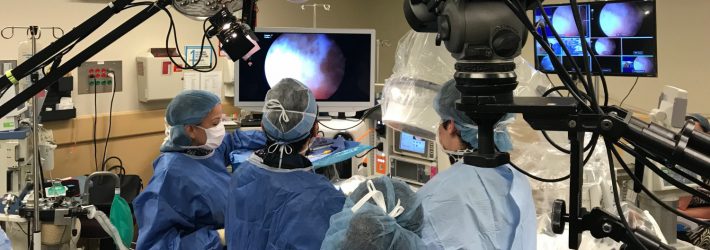

Directing a subscapularis repair at ISAKOS Congress 2015 in Lyon, France

However when it comes to the live surgical event, the exact same practice is not typically the best. Sure it is optimal that the video mixer station is located outside of the operating room. But specifically, I am pointing at the position of the director sitting next to the mixer with the array of monitors, calling the shots remotely, away from the camera operators.

What I quickly discovered during my first live event many years ago is that as a director for live surgical broadcasts as well as live cadaveric surgical demonstrations, my work is profoundly improved when I take to the “stage” close to the surgeons, within touching distance of my cameramen, and not behind the array of monitors with the video mixer.

Prerequisite: Surgical Knowledge is of Utmost Importance

I better start here. One attribute that a director of live surgical events needs is not just familiarity with surgery but an intricate understanding of the sequence of that given surgical procedure being shot.

I know. Personally I have an advantage here, having worked my years as a scrub at so many hospital operating rooms.

There is nothing that surpasses knowing the procedure as thoroughly as possible and knowing what the surgeon audience wants to see. This does not seem to be a divine gift showered upon your average cameraman. Individuals with a surgical eye are rare in this country much less the world. So surgical video experience coupled with studying the procedure is key for any director.

Have the procedure mapped out from A to Z and know your camera angles. A good director knows when camera angles have to adjust and when shots have to zoom in or out before the changing stages of a procedure occur. This is difficult for anyone sitting in the cloud of the unfamiliar, and it is yet a challenge for those who are familiar. You may be the most awarded studio director in the world but that doesn’t mean you can call a live surgical broadcast, and not have the surgeon audience snicker about your missed shots or odd angles.

But if you are one who possesses this knowledge—and I have met several individuals who possess the surgical eye naturally—consider this technique I am about to describe to you. Otherwise simply take your usual seat behind the array of monitors because this technique will likely not make a difference if you do not possess above average surgical knowledge.

The Problem with Live Surgery

In 2011 I was sent to Rio De Janeiro to direct the live surgical skills demonstrations for ISAKOS Congress (International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine).

I had already worked out my walkabout director technique for shooting live surgery many times, but this would be the first time I would have an entirely non-English speaking crew. Yes, not a single English speaker! But they would at least provide me with a translator. Still not good at all for calling shots quickly.

The problem I faced with live surgery is that most cameramen, even those that have shot scores of surgery, don’t know what they are really looking at, nor can they follow what the surgeon is talking about in order to anticipate a shot or camera angle change. “It all looks like a ham-hock to me,” muttered one cameraman. Asking for a shot where the frame touches the glenoid rim and favors the anterior capsule typically gets met with a rolling “huh?”

When cameramen don’t know what they are looking at they too often go wide with the shot. Surgeons on the other hand want detail.

And especially with the detail of orthopedics, I have found it too difficult describing the shots I want from a distance. Camera angles mostly need to change in a flash.

So I use a technique where I prep the cameraman before the shoot. I ask him to step to the side when he sees me coming close. I quickly get the shot, then I back off and leave it with him. This dance is essential, as it takes much too long to describe or indicate the shot or focal length in the heat of a live event. Sometimes we have the time to adjust so I will talk the cameraman through it. But I have never run into a cameraman that wasn’t more than accommodating about this. Surgery is such a specialized area of expertise. How could they possibly be expected to know?

So again considering Rio De Janeiro. I had to bear in mind the extra time it would take to talk through the translator. As well, last summer in Lyon, France, my two cameramen did not speak English either, although my mixer board engineer did.

Walkabout Director’s Critical Tool

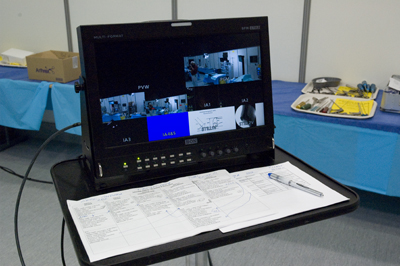

At the center of this technique for liberating the live event for the walkabout director is one key ingredient: a second mixer-board multi-screen set on a rolling stand of some kind so I can call shots while also remaining in proximity to cameras and surgeons. The engineer still has his multiscreen, but I get a mobile second one and a tele-com.

In this example you see the multi-screen I used while shooting live cadaveric surgical demos in Lyon. The main mixer-board was actually in another room, in proximity to the massive distribution network needed to feed the many simultaneous rooms at the meeting. It was control tower central and our lab studio was but a spoke in a great turning wheel.

Fresh setup – 5 surgical demo stations at ISAKOS Congress, Lyon

We used five demo stations and would move from station to station, sometimes neck-to-neck without pause or a break. So the whole space was designed so that we could move with alacrity. Cables were organized for reach and we made sure there was little or no rolling over cables with dollies and jibs. My multi-screen station was a savior as I could quickly check all camera angles, and I could keep it mere feet away from the cameras so that I could jump in and adjust within seconds.

Each station had a program monitor showing the operating surgeon the shot that was being sent to the audience.

If I had to direct from the mixer-board I would have been waiting for a translator to tell the cameramen how to get the shot. We would have been waiting, waiting, waiting, and surgery does not wait. I would have not been able to simply jump in and indicate the angle I wanted to see. Nor would I have been able to join the cameraman at his camera monitor and point to the anatomy I wanted centered or been able to hand gesture for a zoom. I found that the universal use of hand language was easy for everyone.

So now, as far as I am concerned, when it comes to surgery, the only way to direct is the walkabout method, in the OR or on the floor of the lab.

Some hospitals want as few extra people in the operating room as possible. No problem. I’ll just take over one camera for the whole job but still use a rolling multi-screen for calling shots.

A Word On Sterile Technique

Needless to say it behooves the director to know the principles of sterile technique or at least what not to touch if he is to go dancing around an operating room with a live patient. Sensitivity to not contaminating the sterile field is an important protocol that could otherwise get you kicked out of an operating room faster than you can zoom in for a close shot.

So What Happened in Rio?

In Rio, since no one spoke English except for my translator, the day before the live shoot we all gathered around and I used the translator to pore over details. I prepped the crew on how I would hand gesture what I wanted them to do. I went over some instrumentation in detail, how an orientation to the tips of instruments is generally desirable, and we mocked the shots the day beforehand. We took our time and what was most critical was that the mixer operator could at least understand some basic English, like “camera one now,” or “standby for scope.”

The mixer operator turned out to be fabulous. I couldn’t believe it. He could barely form an English sentence but with practice he was like a bald eagle at salmon season watching and listening. He did not miss a beat. It was a prize moment.

Since then, I have conducted several international, non-English speaking crews. But with a little prep and with this technique, live surgical video proves a thing of utter beauty.

I am sure there are still many procedures that can be managed with the director at the mixer board, such as cath procedures or those procedures where only fixed cameras are used. But if you really want to shine and you have the surgical know-how, give this technique a try. And please get back to me on it. I would love to hear from you!

_________________________________

SUBSCRIBE to the Plexus YouTube Channel for how-to updates on surgical video production and editing techniques.

See this article on LinkedIn at The Walkabout Director or Creative Cow.